Last week, BRIN announced its palm oil-based biochar research initiative, highlighting their advanced characterization facilities, including a 700 MHz NMR, reportedly one of the most complete spectroscopic laboratories in Southeast Asia. This is genuinely exciting for Indonesian materials science.

Last week, BRIN announced its palm oil-based biochar research initiative, highlighting their advanced characterization facilities, including a 700 MHz NMR, reportedly one of the most complete spectroscopic laboratories in Southeast Asia. This is genuinely exciting for Indonesian materials science.

But reading the announcement, I found myself thinking about a persistent gap in our field: we’re getting very good at characterizing biochar, and reasonably good at understanding pyrolysis chemistry. What we don’t talk about nearly enough is the engineering reality of producing biochar at industrial scale.

The translation problem

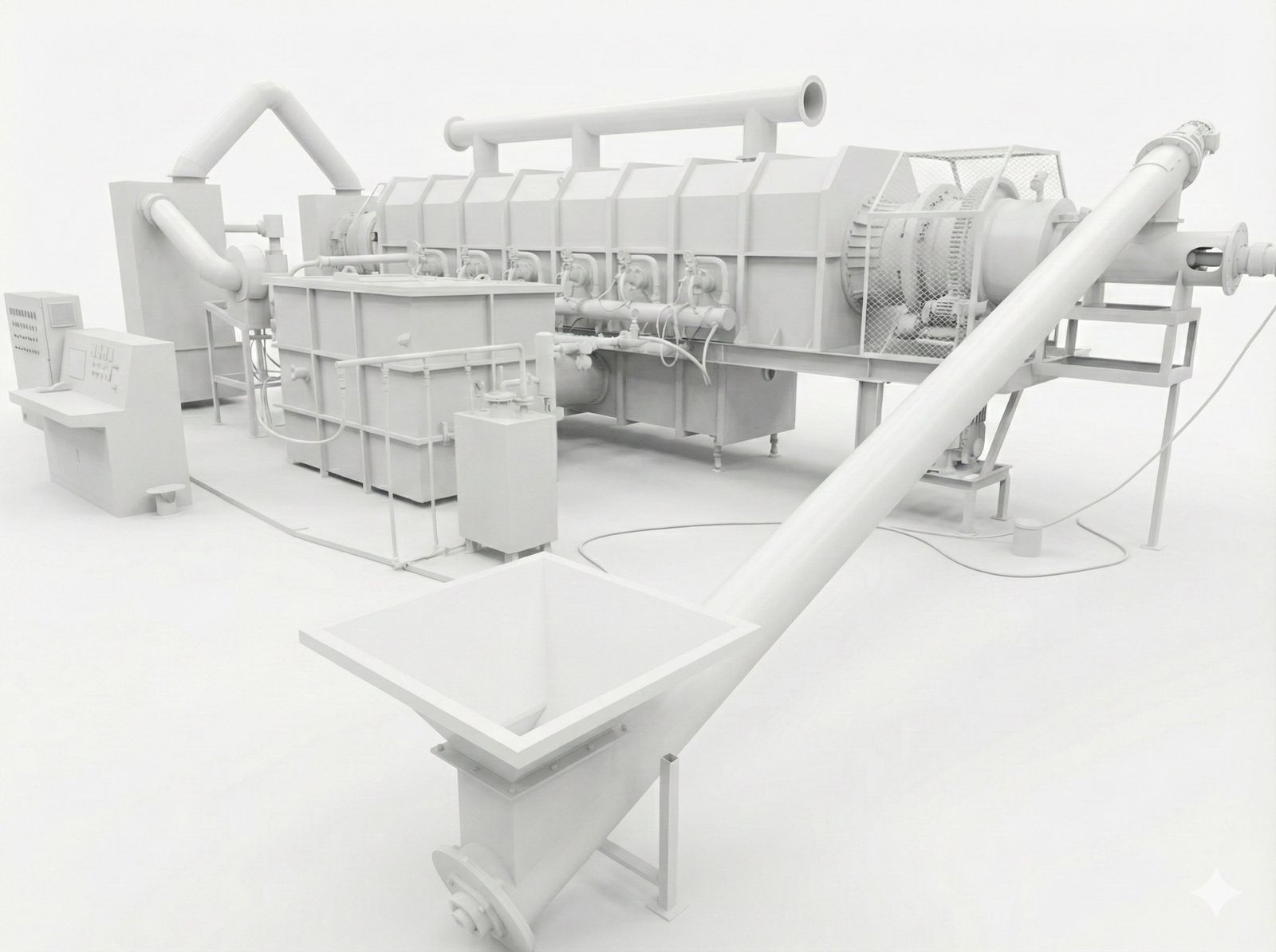

A recent paper in the Journal of Cleaner Production put it directly: laboratory-scale demonstrations of thermochemical conversion are intended to inform industrial production, “yet little work exists to translate laboratory findings to pilot scale and beyond.” The authors found that industrial systems like rotary kilns and auger reactors “may induce more significant heat and mass transfer limitations than laboratory scale experiments.”

This isn’t a minor footnote. It’s the difference between a process that works and one that doesn’t.

In laboratory pyrolysis, you control everything. Small sample sizes mean uniform heat distribution. You can precisely regulate temperature ramps and residence times. The feedstock is typically dried, homogenized, low-ash, and behaves predictably.

Scale that up to processing hundreds of kilograms per hour, and the physics change fundamentally. Bulk density shifts during carbonization, affecting auger torque and material flow. Silica in agricultural residues causes slagging and fouling that never appears in crucible tests. Pressure dynamics become difficult to predict.

What the literature doesn’t capture

The peer-reviewed literature is rich with studies on how pyrolysis temperature affects biochar properties, how different feedstocks yield different carbon structures, how heating rates influence surface chemistry. A recent review in Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering noted that while “numerous reviews have addressed both established and new biochar production techniques, they frequently overlook a detailed analysis of their strengths and limitations for large-scale production.” Similarly, a comparative study of reactor types found that “literature comparing the influence of the reactor type on biochar properties was very scarce.”

Where the knowledge lives

The knowledge about how specific feedstocks behave in specific reactor configurations, about managing moisture-related pressure dynamics, about the subtle interactions between residence time and syngas flow: this knowledge exists. It lives in equipment manufacturers’ iterative design modifications after field failures. In operators’ learned adjustments. In the troubleshooting conversations that happen after something goes wrong.

One equipment developer has noted that “most auger pyrolysis kiln manufacturers must modify their auger assemblies multiple times to overcome various failures” and that “once a particular design works, it cannot be scaled to a larger capacity.” That’s hard-won knowledge. But it doesn’t circulate the way published science does.

Much of this operational insight remains proprietary, understandably so given how expensive it is to acquire. The cumulative effect, however, is an industry where each new entrant must rediscover the same hard lessons, where the same mistakes get repeated, and where the gap between laboratory promise and industrial reality remains wider than it needs to be.

Why this matters now

The biochar industry is at an inflection point. Carbon removal markets are creating demand for industrial-scale production. Climate commitments are driving investment. But as one industry analyst recently observed, “the biggest blockers to scale are rarely technical or scientific. They’re buried in logistics, operations, and execution.”

When a standardized reactor meets a feedstock it wasn’t designed for, the problems aren’t abstract. They’re pressure spikes, clogging, slagging, inconsistent product quality, and in serious cases, equipment failure. These aren’t failures of chemistry. They’re failures of engineering translation.

What might help

I’m genuinely uncertain about the path forward here. But a few possibilities:

More pilot-scale research with realistic feedstock variability. Laboratory studies typically use dried, homogenized samples. Industrial operations rarely have that luxury. Research institutions with characterization capabilities—like BRIN’s new facilities—could add significant value by connecting their analytical work to feedback loops from production realities.

Industry forums for discussing failures without full disclosure. Perhaps there’s space for practitioners to share categories of problems and general approaches without revealing proprietary specifics. Something between trade secrecy and full publication.

Honest conversation about feedstock-reactor matching. Not every reactor design suits every feedstock. The industry would benefit from more open discussion about these constraints, even if the specific solutions remain proprietary.

Recognition that scale-up engineering is a legitimate field of inquiry. Academic incentives reward novel findings about biochar properties and applications, not operational troubleshooting. Shifting this would require funders and institutions to value translation research differently.

The gap between the beaker and the factory floor is where many promising biochar projects have stumbled. Naming it openly may be a starting point, even without clear answers about how to close it.

References:

CarbonZero. (n.d.). Horizontal bed kiln. Seneca Farms Biochar. https://sfbiochar.com/?p=en.horizontal_bed_kiln

Iswardi, A. H., Hubble, A. H., Lehmann, J., & Goldfarb, J. L. (2025). Can batch lab-scale studies of slow pyrolysis describe biochar yields and properties upon upscaling to a continuous auger kiln? Journal of Cleaner Production, 496, 145150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.145150

Kendall, M. (2025, August 6). The myth of easy biochar scale-up. Critically Speaking. https://thecarbonlowdown.substack.com/p/the-myth-of-easy-biochar-scale-up

Loc, N. X., & Phuong, D. T. M. (2025). Optimizing biochar production: A review of recent progress in lignocellulosic biomass pyrolysis. Frontiers of Agricultural Science and Engineering, 12(1), 148–172. https://doi.org/10.15302/J-FASE-2024597

Moser, K., Wopienka, E., Pfeifer, C., Schwarz, M., & Sedlmayer, I. (2023). Screw reactors and rotary kilns in biochar production—A comparative review. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 174, 106112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106112